In every science or field of work, professionals use principles to design high-quality solutions.

Principles, because of their nature, can be reused in other fields of work if they are made accessible and understandable.

Dragon1 structures and reformulates principles in various sciences and fields of work to make them more reusable in other sciences and fields.

Recognizing and understanding principles is important for the architect. By understanding the underlying principles behind the concepts, the architect can make the appropriate choice for the concepts needed, given the company's strategy.

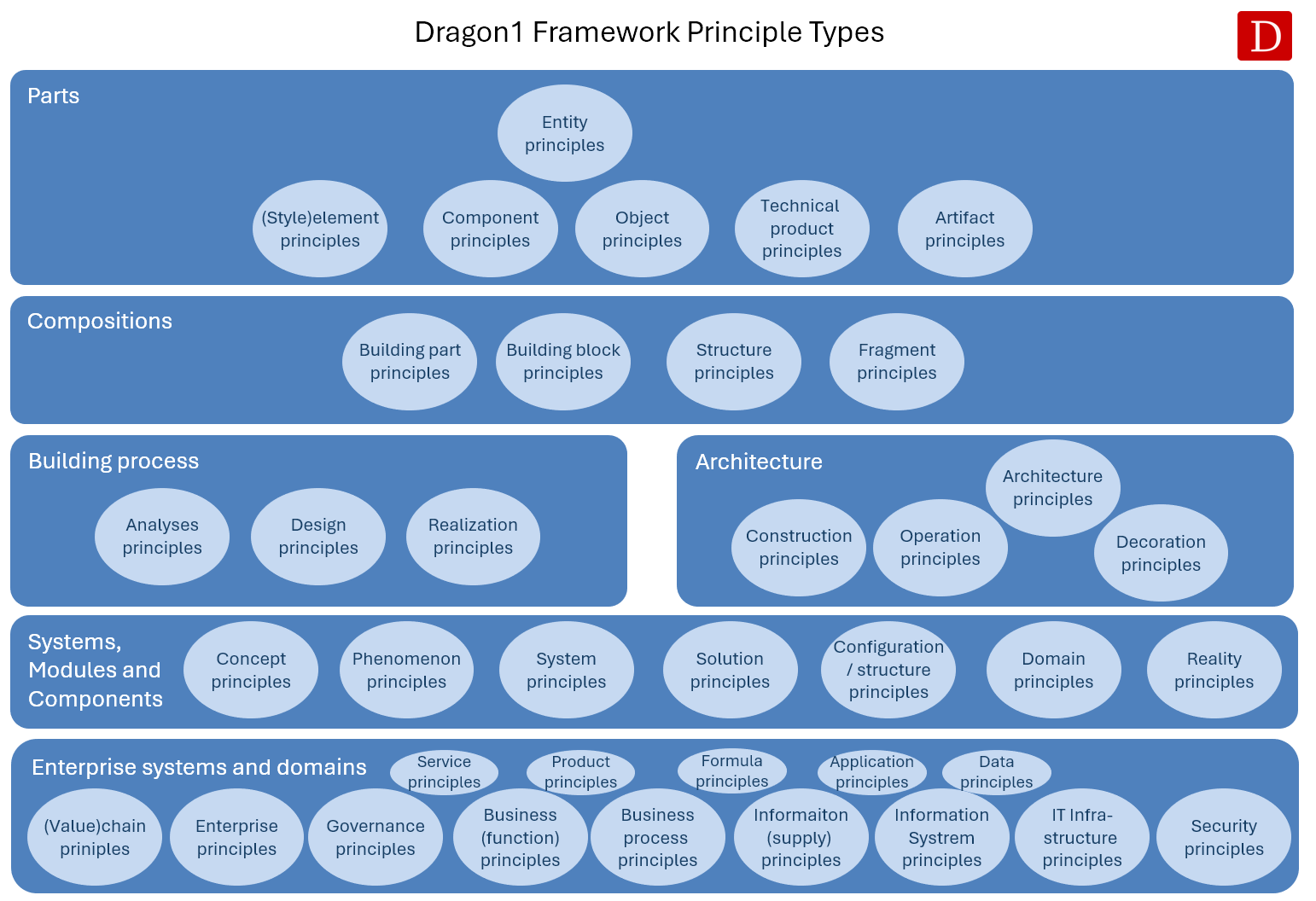

Overview of Principle Types

It is the task of an architect to deliver benefits resulting from working with concepts in the right context and through the right implementation; it should apply in the structure they design. The architect must be very clear about the functionality, consequences, and impact of the results produced by the concepts.

It is also important that the architect understands the ‘what’ that makes a good concept, the enforcement mechanism, and the elements, components, objects, and rules that must be minimally realized. Ultimately, the components and objects are implemented with technical products.

A principle describes the enforced operation of the entire concept or a part of the concept. A principle describes a ‘cause and effect’ relation (by … [this]… then … [that]... happens). Dragon1 calls a principle that describes the entire operation of a concept the ‘first principle.’ An architect needs to find the ‘first principle’ because it allows the essence of the concept to be quickly understood and conveyed.

The principle that describes how a concept works is the First Principle. Principles that describe parts of a concept are called principles.

An example of a first principle is the loose-coupling principle of services: By offering services without the consumer of the service becoming dependent on the way by which the service provider delivers the service, the service provider ensures that the process of service provision can be changed often and better with minimal impact for the consumer so the service of the enterprise becomes more adaptive as a whole.

How does this work in practice? An enterprise needs a webshop for its products and must be coupled to the sales system based on web services. The way a supplier creates a webshop according to a particular technology is less important than all communication based on web services, with unbounded, loose couplings between systems.

Consumers of a webshop are never really interested in how and with what technology a webshop is constructed. They want to know which standard interfaces or protocols are used for communicating with the webshop.

Suppose the supplier of the webshop, for various reasons, changes over to a new website platform or another version of the webshop. In that case, this can now have only a minimal impact on the buyer of the webshop. This will be the case as long as the loose-coupling principle, which enables communication between systems, remains operational.

Sometimes, a concept is so elaborate that it consists of part concepts that are independent in their own right. This means that principles apply to the part concepts as well.

Figure 1, Example of the types of principles present in the entities of an enterprise. The model Types of principles shows an example of how different types of principles can be classified. There are more principles demonstrated in the model than mentioned on this page. The ‘why’ and function of these principles can be derived from the following principles covered in the other pages.

The architect usually looks at four principles to maintain control over the quality of the structure he designs. This concerns the concept principles, the system design principles, and the principles of the yet-to-be-designed systems. Also, the architect examines principles in other areas to learn from and identify candidate principles for reuse.

Dragon1 recognizes different principles for the architect to apply a specific principle most efficiently and purposefully. By principles, it is essential to realize that everything revolves around whatever principles already exist and have been determined; in other words, which result belongs to or is produced by the principle.

It must be recognized that a client sometimes wishes or even demands (in terms of requirements) that a certain principle is taken or is to be taken into account. Requirements will then be labeled as principles. However, requirements are listed in the requirements table, and principles are integral to the architecture. In the table of requirements, certain principles can be demanded. It is essential to keep them well apart.

If it is not known yet which consequences a principle has or produces, but the principle is already formulated, then it is often a hypothesis or axiom. A hypothesis is a claim that still needs to be proven; an axiom is a generally accepted hypothesis that can be negated at any moment. A (scientific) principle is, to all intents and purposes, difficult to negate for hundreds of years.

It is also possible that rules, the agreement between two or more parties, are labeled as principles. An agreement, however, does not say anything about the degree to which it is maintained, as opposed to a principle. An agreement does not dictate the degree to which a person can expect everybody to keep to the agreement.

Contrary to those mentioned above, in law, however, this is the case that one may rely on an agreement being maintained. With rules such as regulations and directives, this is not the case.

An example of a rule, which is labeled as a principle and which is used as a principle, is 'a single request for information': ‘We only request our clients to provide certain information only once, and we administrate these (details) in such a way that we can always reuse them later without having to send another request’. This appears to be a good principle, but it isn’t a principle; rather, it is an assumption, rule, or requirement. There is an agreement on how this should always transpire. However, it appears from this statement how the contract will be enforced. For it to always be valid. It also seems from this statement that the frequent reuse of this information is. Why would this enterprise invest in developing a system that achieves all this?

When an architect looks at this rule, he can discover the intended principles: the principle of ‘lower cost through reusing information’ and the principle of ‘efficiency by reusing information’. By administering the information only once and then reusing the same information, it ensures that the enterprise saves time by avoiding repeated administration of information and by making fewer mistakes, as holding incorrect versions of the information will be less likely.

Concept principle

A concept principle is the explanation or description of the enforced operation of a concept, creating a certain result. A concept principle is also referred to as the operational principle of a concept.

The principle of ‘modularity’ is an example of the constructive technological concept of ‘modular construction’ principle. Customers increasingly require their suppliers to provide solutions that offer maximum flexibility. The principle of modularity can be described as follows: ‘By always producing solutions from an environment of robust quality control on individual specialized and optional components, which can be assembled quickly into various combinations, it can be assured that solutions will emanate from different people at different locations. This allows the supplier to meet customer demand for maximum flexibility. An architect often chooses a modular solution when a customer demands flexibility.

We also note how a principle can be formulated with the assistance of specific sentence constructions to describe the maintained operability of a concept. With the aid of this formulation, we also note which elements and components make up a concept and which rules apply.

The concept must explicitly mention how the operation is enforced, as only then will it become clear when the principle is applicable and in which context. The success of an enterprise depends on the degree to which a concept is enforced and adequately implemented (within the enterprise).

A concept principle is a principle that shows the way a concept has been put together, how it works, or what has materialized in the concept, from which a certain result is always produced or a certain effect is noticeable.

Design principle

The architect creates architecture designs of structures. The architect utilizes certain principles in his designs to create a high-quality structure. Dragon1 refers to these principles as design principles.

An example of an enterprise design principle is: ‘the principle of independence by way of service procurement’. The design of the operating model should prioritize the procurement of services over highly specialized technologies, solutions, or products. This way, the enterprise remains independent of the underlying technology, solutions, or products related to the procurement services.

An example of an information design principle is: ‘to incorporate a hosting provider’s groupware solution, which links internal information systems via a generic XML interface. First, the supplier incorporates GroupWise and then changes over to MS SharePoint. To the customer, this means a different user interface and increased functionality. The supplier must transfer data and structures in accordance with the XML interface definition. The customer himself does not require knowledge of the underlying technology of the groupware service that has been procured. This is a prime example of sustainable procurement while reducing dependence on technology.

An architect must choose design principles that realize or meet quality requirements, strategic starting points, and preconditions of the envisaged structure. A constraint is that all matters related to the client’s/owner’s mission, vision, identity, culture, and preferences are appropriately translated by their requirements. Principles in phenomena, concepts, and existing systems serve as models of design principles.

All acceptable architectures consist of a myriad of design principles. Architects should limit, as much as possible, inventing their creative design principles and, as much as possible, incorporate best practice design principles. This will provide knowledge, assurance, and predictability while applying design principles. They have already been tried and tested.

Dragon1 recommends identifying architecture design principles in each accepted architecture in an architecture framework. This applies to all types of principles.

A design principle is a principle that applies to the environment of a structure and, as such, influences the structure. The architect must consider these principles when designing and realizing a structure.

Architecture principle

By recognizing architecture principles, the architect can strip concept and design principles from one structure or a certain discipline of its context to reuse the principles in another structure or as part of another discipline. As such, an architect can couple different architecture principles with each ambition and each strategic starting point of an enterprise. This way, the architect ensures that strategy constitutes the basis for architecture throughout the entire enterprise.

An example of an architecture principle is: ‘information leads to knowledge, and knowledge leads to power.’ This principle is applicable everywhere. This applies to people, software systems, and enterprises. The principle dictates that if an enterprise possesses more information than other enterprises about a certain subject, then the enterprise can make better decisions regarding this subject. And if someone can make better decisions about a subject, they will be given higher responsibilities. Architects primarily use architecture principles to organize design principles and cluster them at a higher level of abstraction.

An architecture principle is a concept or design principle devoid of all contexts or a design principle that can always be used everywhere in a particular system. An architecture principle is a universal principle applied in the holistic enterprise and, therefore, a comprehensive statement about the ’construction’ of the enterprise.

Reality principle

Reality principles state what is valid in a system that has yet to be designed or realized. With a reality principle, the enforcement must be stated explicitly to make the principle valid. This is contrary to design principles. Design principles dictate what is valid in the context of a system that has yet to be designed. With design principles, the yet-to-be-designed system already incorporates enforcement within its context.

The reality principles state how the enterprise concepts behave. Hereby, the architect can identify fundamental inter-relational flaws and resolve them permanently. An architect often faces a complex mix of real-world principles, which can perpetuate certain undesired situations. A clear view of this makes finding solutions to design issues much easier.

Dragon1 differentiates between AS-IS and TO-BE reality principles. AS-IS reality principles, desired or undesired, are already present in an existing system. On the other hand, TO-BE reality principles are principles that will be applied in a system.

TO-BE reality principles are different from design principles, as a design principle covers an operational mechanism, and it is also applicable outside the structure that will be designed. A reality principle only applies to the operational mechanism of a yet-to-be-designed structure.

An example of an undesired ‘AS-IS’ principle regarding enterprise activity is: ‘because our products are not supplied with accompanying digital information formats, additional costs will be incurred for printing information media, resulting in lower profit margins’. Naturally, the enterprise wants to improve on this principle.

An example of a design principle regarding enterprise operations is: ‘By supplying our products with digital information, it is ensured that the costs at the point of sales are lower, resulting in higher profit margins. This principle exists outside the enterprise, even before they begin designing an architecture.

An example of an enterprise's ‘TO-BE’ business reality principle is: by always providing digital information about our products and providing them via the Internet, our business enjoys lower sales costs, resulting in higher profit margins. This business reality principle only applies over time in the business.

It pays for an architect to know which reality principles are at play in all the enterprise’s systems and all the elements of the enterprise configuration model. This belongs to the ‘AS-IS’ architecture and the enterprise architecture design.

All being equal, the ‘TO-BE’ reality principles of a system Z that is yet to be realized are parallel on a 1-to-1 basis with the ‘AS-IS’ reality principles of the TO-BE realized system Z. However, in reality, this is not often the case. Because ‘TO-BE’ reality principles are sometimes not used properly, or a system has not been realized properly, which can lead to wrong and/or new principles being applied to the structure next to intended reality principles. Another reason is to take stock of the principles that emerge in reality in every structure and to match them with the principles used in the design of the architecture.

An architect needs to know the current situation in an enterprise regarding principles, especially if an architect wants to assist the enterprise in getting rid of persistent, wrong principles. Therefore, the architect must know exactly which principles are valid, as well as what and who enforces these principles, and understand which elements they consist of and why the effect or result of these principles does not contribute to realizing a strategy.

For all architectures in an architecture framework, the architect must have a top ten ‘AS-IS’ reality principles, design principles, and ‘TO-BE’ reality principles. Every architecture design the architect makes will require these principles as a framework.

A reality principle is a principle that states what the enforced way of working is within a realized system (or part of that system). In this case, a reality principle refers to a principle that applies to the current situation within an enterprise.

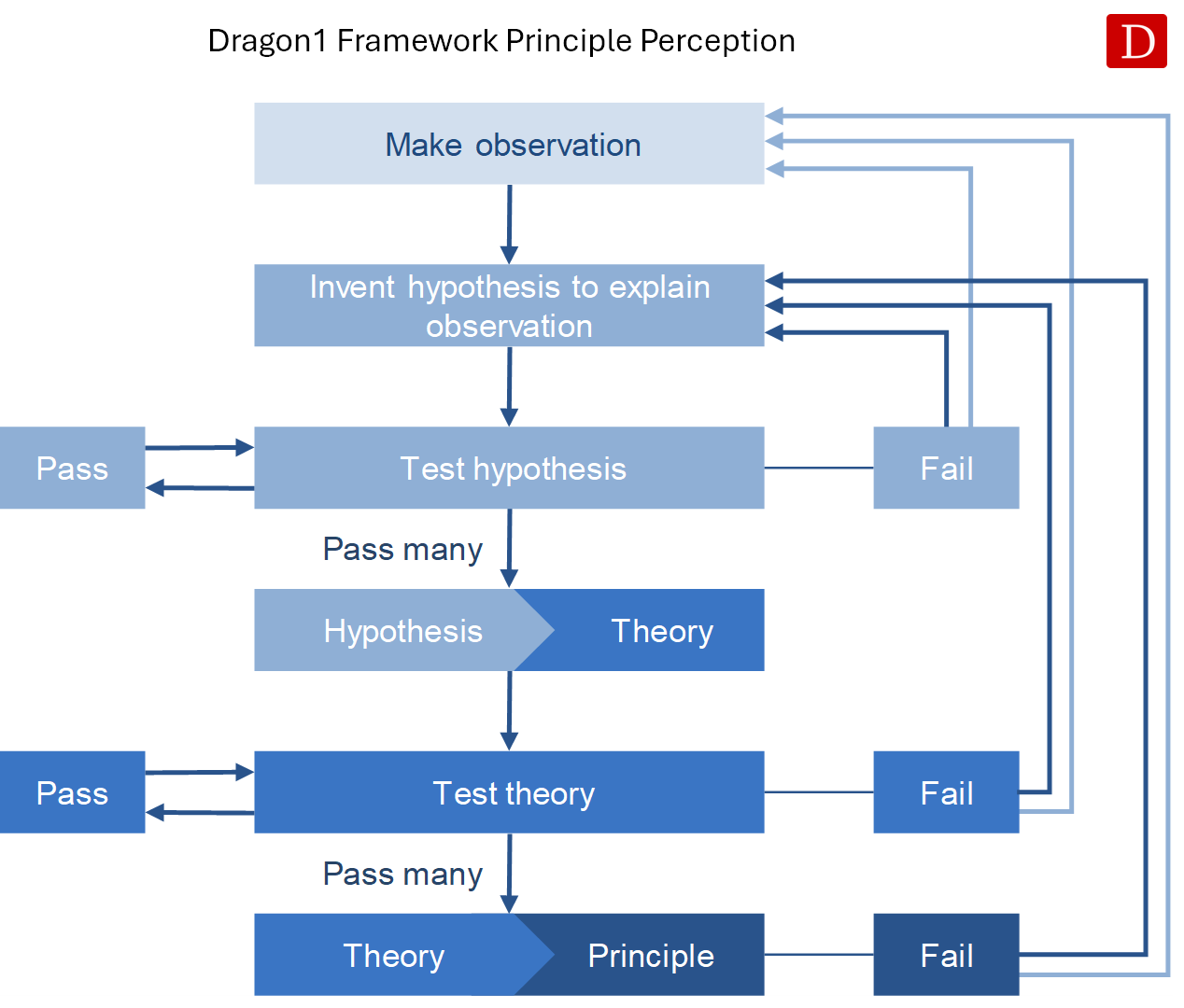

Perception of principles

In this paragraph, we describe how architects can perceive principles, concepts, and certain phenomena and identify them in different systems. The following systems are considered: nature, enterprises, and structures.

To create an architecture design, it is important to identify principles. It requires knowledge, experience, and the ability to recognize principles and study them. Once an architect identifies a principle, it becomes easier to utilize it in an architecture design or as a criterion for selecting a concept.

Figure 2, Example of the perception principle framework. The Perception of principles model shows an example of how, by way of testing and honing statements, an architect can arrive at a correctly formulated principle. The architect’s knowledge, experience, and ability regarding business administration and information technology determine which principles, operational) working of systems, concepts, and phenomena he perceives as important, and which questions he needs to pose regarding the principles.

Regarding the perception of principles, Dragon 1 considers the context of these principles. The context may vary, consisting of all situations, environments, and locations.

Situations

The architect includes in his architecture design the various situations within an enterprise. An example of a working situation is the daily work routine, consisting of arriving at the workplace, logging in, and starting up an application. An example of a user situation is sitting in the canteen at lunch, requesting a building permit on the internet via a PDA to build a structure extension to his home.

The architect must also differentiate between the physical and digital user and work situations. An example of a user situation is a session for ordering a book online. An example of a work situation is when an application for a Social Security payment is approved. Every situation unfolds within a timeframe, ranging from an instant moment to a period of time (a longer period). A period spans a relatively long time. A moment occurs in a relatively short period.

A user situation is a moment in time whereby the user of products, services, and goods plays a prominent role. It involves a certain relationship, coherence, and association with other actors in the context of an environment.

The architect must differentiate between situations, environments, and sites because customers and workers use different resources, facilities, and infrastructure at different moments and in different ways. These activities pose indirect demands, while people pose direct demands in a work situation. For instance, at the employee’s place of work, different rules apply than in a user situation at home via the internet. Different rules apply to an office location or a home location. Different rules apply in an office or a factory than in a user environment on the street.

A work situation is the user situation of an employee. A user situation is a situation of the customer.

The structures designed by an architect, such as businesses, information facilities, and IT infrastructures, are used in different situations, environments, and locations. During the design process, the architect must be well aware of these situations, environments, and locations to analyze them as a context in the architecture design.

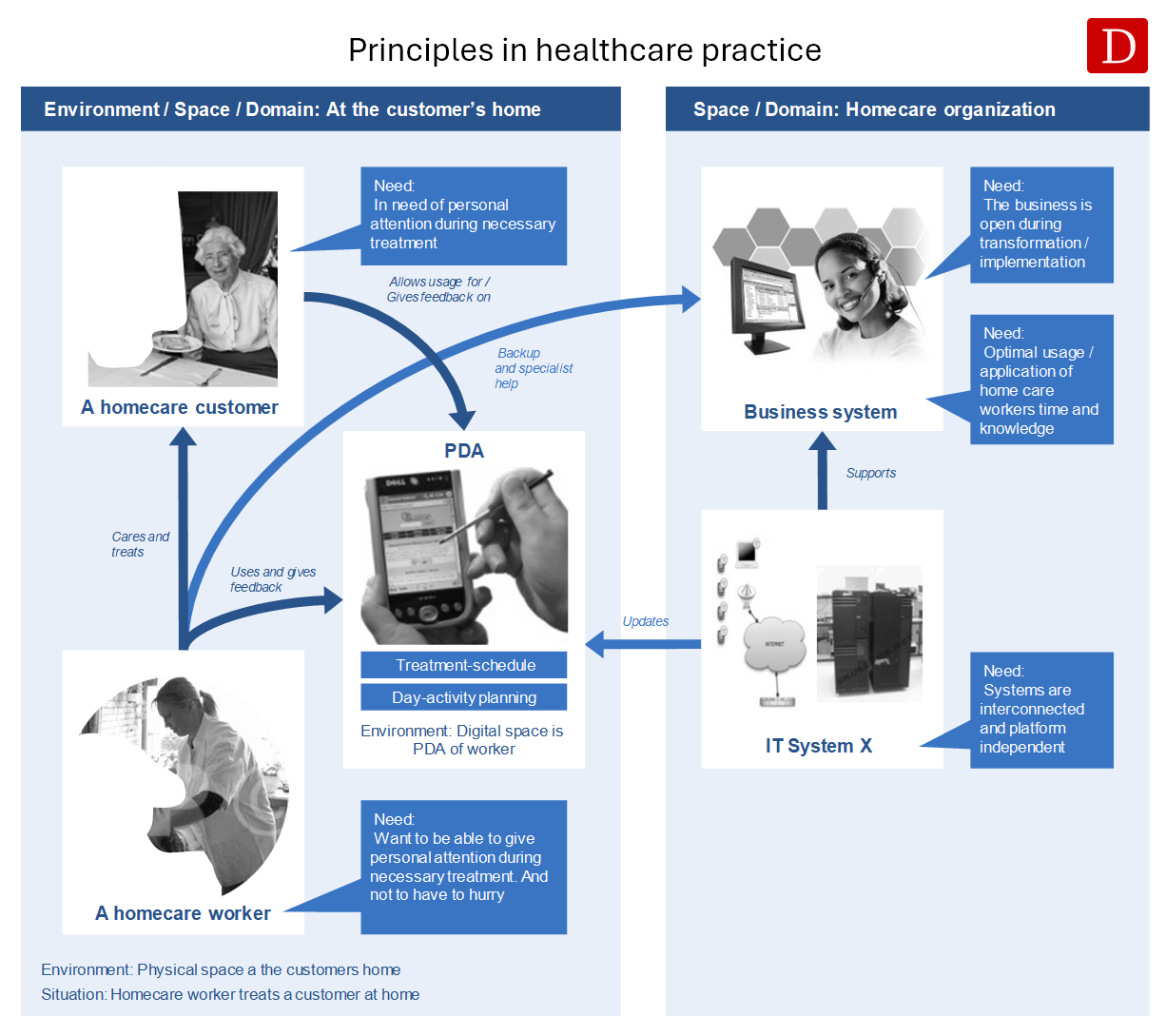

Figure 3, Example of framework principles for healthcare practice. Figure 3 shows an example of different situations, environments, and locations. It depicts a situation in which a solution of chain reversal and personal planning of activities by another person (an employee) is made possible with a PDA (Personal Digital Assistant – essentially a comprehensive mobile telephone).

For instance, in the case of a care provider at a patient’s home, a care provider can use a PDA to work more efficiently. To make the solutions work more efficiently, the architect needs elements and components necessary to the concept of visualizing reverse care activity planning indicative of an in situ situation.

In Figure 3, it becomes clear that the PDA uses a network and database server to obtain planning and activities, and allows the care provider to revert to a staffed support center. It then soon becomes obvious which demands the PDA has to comply with regarding availability, security, robustness, convenience, and comfort of use.

An architect should always consider three different situations: an average situation, an exceptional situation, and an extreme situation. He needs to include these situations in his design. Normal and extreme situations will occur at various times and periods throughout the day, week, month, or year. A system must be designed accordingly and in such a way that it remains responsive to such situations and provides the desired and predictable services at all times.

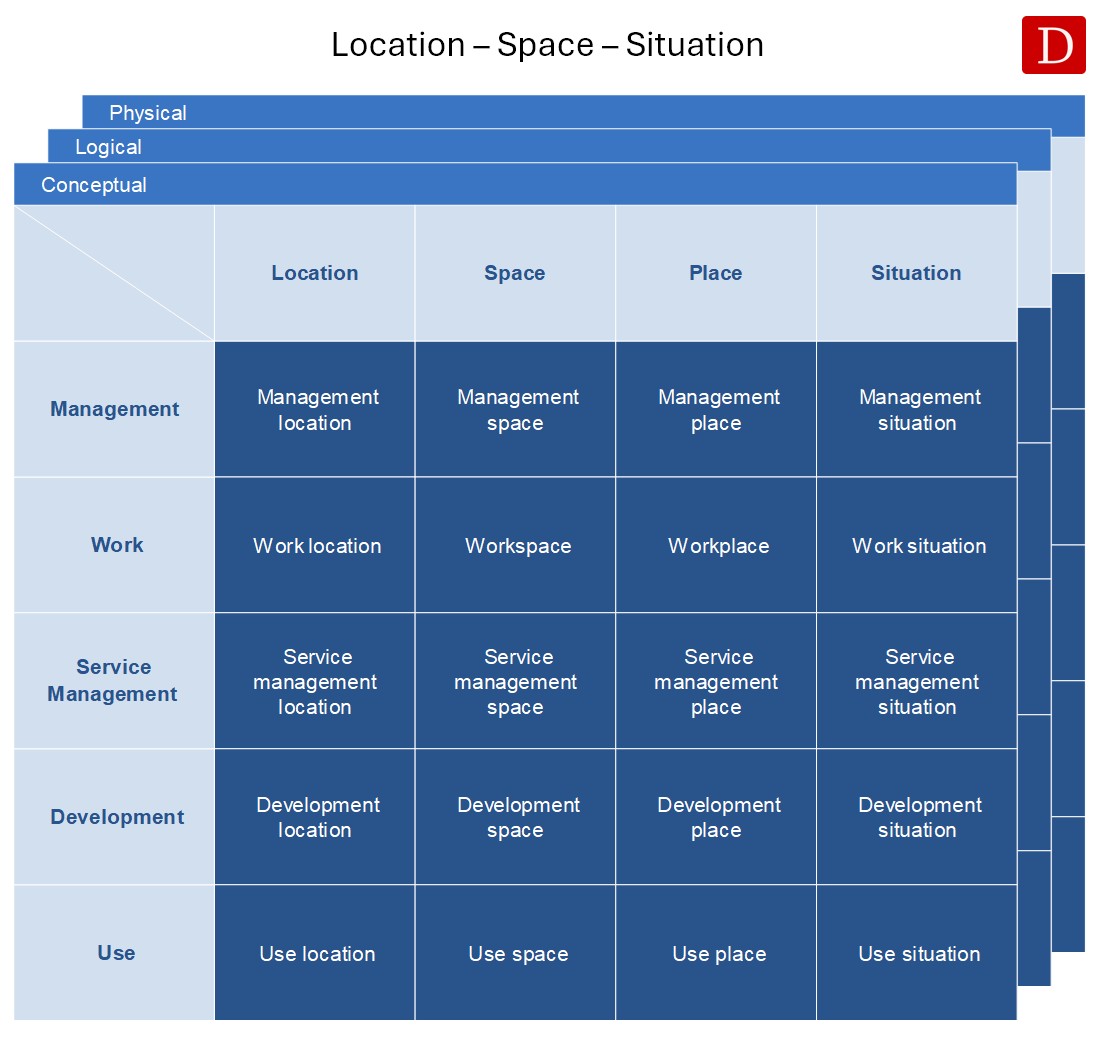

User space and work space

Situations always take place in certain spaces. These can be physical or digital spaces. Physical spaces at work are, for instance, the counter, the department, or the back office. A digital space, for example, includes a social network, the intranet, a groupware environment, or a business system.

A user space is a protected environment where users can access certain resources, facilities, and infrastructure. A user space is primarily meant for customers. A workspace is a user space meant for employees.

Locations (Environment / Sites)

All structures and structural parts that an architect designs exist at one or more geographical locations. Even if everything can be done digitally or virtually, many architecturally designed solutions are still not 100% independent of place, time, space, and situation. Therefore, the architect must include these structural dimensions in their design.

A location is a geographical place where there are user spaces and/or workspaces and where user situations and work situations occur with customers and employees.

An architect designs situations, locations, and spaces that he created primarily with resources, infrastructures, and facilities; as such, various situations could take place in these spaces and locations by way of, for instance, predefined scenarios.

Figure 4, Example Framework of Location Space Situation. The model location-space-situation incorporates a diagram that shows which types of spaces, locations, and situations an architect can identify from a generic point of view. The more the architect recognizes these dimensions, the better the architecture design becomes. Say that an information system is used by customers, managers, administrators, developers, and operational employees. Then, it is important to identify the types of actors for these target groups. The actors determine which spaces and at what location the specific demands regarding information systems are made.

Enforcement Mechanism

As mentioned before, a principle is an enforced working of a concept, structure, or phenomenon. Because a principle is an enforced activity of a concept, structure, or phenomenon, the architect must explicitly mention the part responsible for enforcement when describing the principle. The more an architect understands the element that governs the enforced activity, the better they can implement principles.

An enforcement mechanism is the total sum of the internal and external elements that take care of the consistent way of working on a concept within a given context.

There are different types of enforcement, for instance, the built-in enforcement with people, such as ethics, decency, and the value of civilized behavior. In nature, the powers of nature take care of enforcement. As for systems developed by humans, specific constructions and functions are in place to enforce them.

Because enforcing a principle could fail, Dragon1 discusses the probability that a principle works in a certain way. The probability factor that a principle works in a certain way is greater than 0.7 (>0.7) Architects must be aware that enforcing a principle is the responsibility of individuals and that it is possible that a principle may not always work in the same way.

Everybody faces different enforcement mechanisms daily. For instance, human conscience and discipline enable humans to conform to culturally, socially, and legally bound rules. Conscience and discipline often compel someone to react in a certain way. However, conscience and discipline are not infallible.

Where conscience and discipline fail, the authorities use different forms of enforcement, for instance, police with cameras to detect and punish law violations to ensure that something that is required to function or needs to take place is only temporarily disturbed.

Enterprises have their ways of applying supervision and enforcement, which are necessary to ensure that certain principles are applied and maintained. In this case, we consider the security of a structure where only people with a pass are allowed access, or agreeing to a project budget for an information system only after an approved business case has been published.

Rationales

In a structure, we can find different principles in force. These principles work for a particular reason. The underlying reasons for the way these principles work in a particular way are defined by the Dragon1 method as a 'Dragon1 rationale'.

In a rationale, a context often reappears. Outside this context, a principle hardly ever works. The enforcement mechanism is not effective in this instance. By examining, for instance, the reality principle, it becomes clear why certain design principles and conceptual principles do not work in practice within an enterprise.

An example of a rationale is that the success rate of an IT project will increase only if there is strict adherence to receiving approval for the business case of a project start-up. However, if there is little to no knowledge of writing a business case, it won't be easy to set it as a precondition for project start-up. It is the architect’s task and responsibility to identify areas where knowledge is lacking within an enterprise and to assess the availability of expertise.

A rationale is the basis that underpins the way a principle works the way it does.

Phenomena

Dragon1 also recognizes phenomena next to concepts and structures because the architect needs to consider that they will appear sooner or later. A phenomenon is a fact or situation that is observed to exist or happen. Phenomena not only apply to situations such as a storm, rain, or electricity interruption but also to customer loyalty, ‘dilapidation’ in terms of the deterioration of a system that has not been managed or maintained properly and it could also apply to ‘an increase in complexity’ – caused when the mutual dependencies between elements of a system are unnecessarily high.

An architect sometimes has to defy the laws of nature: he has to make an architecture design of a safe, open, flexible, and stable structure. The architect, therefore, must also understand and control principles in a phenomenon that will interact with a yet-to-be-designed structure. The architect must also consider exceptional situations in which certain phenomena may exist.

For instance, we look at a computer network. It may happen that employees, for whatever reason, request the same file simultaneously. An architect typically designs a network based on three scenarios: common use, light use, or heavy use. However, network design usually does not consider the next two situations: ‘extreme excessive use’ and ‘never-used’. When a situation arises with extreme usage, there is a significant problem of waiting times and file-locking conflicts.

With phenomena, we can predict events and behavior. That is why an architect must know the phenomena that appear near and within a structure. An example of a phenomenon is chaos. If one does not demand data quality within a system, the database will become unfit for purpose quickly.

The architect has to use and must have knowledge of phenomena and protect the structure accordingly. If only we were to look at an enterprise from a phenomenon's point of view, it would produce some interesting insights.